Helping harm reduction programs move towards best practices

For harm reduction programs across Canada, the distribution of injection, smoking and snorting/sniffing supplies remains a crucial activity to reduce drug-related harms. While estimates of the number of people who use drugs from unregulated markets are imprecise, the evidence that does exist suggests that more than 170,000 Canadians inject drugs and 730,000 used cocaine or crack in the past year (1). Population estimates of the number of Canadians who used crystal methamphetamine are not available. The rates of needle/syringe sharing in Canada have dropped in the past 20 years to just over 10% among people who inject drugs, but more than 30% reported re-use of other injection-related equipment.

Since the late 1980s, when the first needle and syringe program pilot projects were launched in Canada, the distribution of harm reduction supplies and education has expanded in scope and volume. This is largely thanks to the availability of provincial distribution programs in some regions of Canada, and the contributions of harm reduction workers, including workers with lived experience. The goal of the recently launched and newly updated Best Practice Recommendations for Programs that Provide Harm Reduction Supplies to People Who Use Drugs and Are at Risk for HIV, HCV, and Other Harms is to help programs move towards best practices, if these are not already in place.

What’s new and different from the 2014/2015 versions?

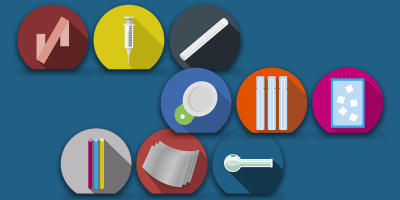

This version focuses only on the distribution and disposal of injection, smoking and snorting/sniffing supplies, including needles and syringes, cookers, filters, sterile water, ascorbic acid, alcohol swabs, tourniquets, safer crack smoking equipment, safer crystal methamphetamine smoking equipment, foil for smoking and straws for snorting/sniffing. The earlier versions included chapters about ancillary services, such as referrals, testing and counselling. In the 2021 version, we narrowed the focus to the chapters workers told us they used the most. It was peer-reviewed by experts with lived or living experience of drug use, frontline service workers, program managers, provincial distribution program managers, policy makers, knowledge translation managers and scientists from across Canada prior to release.

We updated the pre-existing versions by searching for and integrating any new scientific evidence related to the distribution and disposal of injection, smoking and snorting/sniffing equipment. For example, we added new evidence about hot and cold drug preparation methods (which you can find in the filter chapter) and the importance of heating and cooling drug solutions (available in the cooker chapter) to reduce the number of particles in drug solutions (also, in the filter chapter) and transmission of HIV and other pathogens.

Why this update was needed

Across the country, more people who use drugs are injecting drug solutions prepared from tablets; understanding how to prepare and reduce related risks has become more important than ever.

The unregulated drug supply has also changed since the last time we published this resource and people who use drugs are increasingly moving towards sniffing/snorting their drugs to reduce the risk of overdose. The new Best Practice Recommendations include a chapter about the distribution of straws.

While the ideal program would distribute all the supplies covered in the 2021 edition, an inability to do so should not discourage the implementation of these practices to the best of a program’s ability.

Carol Strike, PhD, is a professor at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, and a scientist at the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute of St. Michael’s Hospital. Her research program aims to improve health services for people who use drugs and other marginalized populations.

References:

- Jacka B, Larney S, Degenhardt L, et al. Prevalence of injecting drug use and coverage of interventions to prevent HIV and hepatitis C virus infection among people who inject drugs in Canada. American Journal of Public Health. 2020;110(1):45–50.