Let’s talk about sex… ed!

Sex education is rarely without controversy.

As a sexual health educator, working with South Asian communities all over Toronto, I see firsthand how sexual misinformation, stigma, cultural and gender norms can all make sex a hard topic to discuss. Lately, however, it seems to be all everyone wants to talk about.

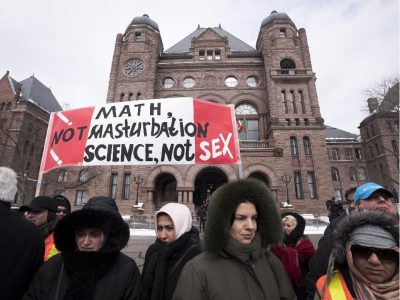

If you’ve been following the news lately, or just taken a lunch-time stroll around Queen’s Park, you may have seen images like this:

In case you haven’t been following the story, here are the highlights:

- The Ontario sex education curriculum developed in 1998 has been criticized by educators around the province for being dated.

- To better reflect our changing reality, a revised and updated version of the curriculum is set to take effect September 2015.

- The changes include educating youth at an earlier age about naming their sexual body parts, talking about gender identity, introducing diverse sexual identities, cyber-bullying and sexting.

- A small but vocal minority has been keen to point out that broaching subjects such as masturbation, dating or sexual and gender diversity may run counter to many family and cultural values.

Parents often hope their children will practise the values and morals that are espoused in the home and distance themselves from conflicting messages. By doing this, we may inadvertently close avenues for meaningful discussions around sexual health. Although this is done with the intent to protect young people, it can expose them to greater risk without the space to ask for guidance. This teaches children that sex is taboo, forcing them to turn to their friends or the internet – which may not be the best source of useful, helpful and accurate information. The taboo also breeds shame, which creates an atmosphere in which sex and sexuality live on the fringes of our communities.

Starting these conversations early teaches youth that sex is a natural part of life. By teaching them about sex, we teach them not to fear it. We teach them that sex can be beautiful and pleasurable. By lifting the taboo, young people can feel safer asking questions, negotiating their relationships and protecting themselves.

Media coverage of this new curriculum and the protests has been quick to pin much of the furor on specific cultural communities, with a focus on South Asians. While it may be tempting to paint such diverse communities with such broad strokes, it ignores the activism and advocacy that happens in these groups. South Asian parents, educators and politicians have all rallied behind these changes, working to educate larger communities about the importance of arming children with the knowledge they need to protect their bodies and navigate their own health.

The folks that I talk to on the ground every day recognize that youth are inundated with sexual images and messaging and that it’s crucial to give them the tools to decipher what they see. By providing a comprehensive sexual education, we are helping young people to develop skills so that they can make informed choices about their health.

Parents, teachers and students alike often dread the talk where sexual body parts, methods of contraception and sexually transmitted infections meet awkward giggles and shifting glances. But the discussion – giggles aside – is an important one, especially for young people who may need information and resources but do not have access.

Suruthi Ragulan is the Women’s Sexual Health Coordinator at the Alliance for South Asian AIDS Prevention (ASAAP) in Toronto.