How Rwanda is eliminating hepatitis C and what Canada can learn from its successes

Rwanda is a country situated in sub-Saharan, eastern Africa with a high population density: 499 people per square kilometre in 2018 and a population of 12.6 million people in 2019, an increase of 2.64% from 2018. Although it is among the poorest countries in the world and experienced a genocide against the Tutsi people in 1994, Rwanda has made immense progress in the fields of public health, achieving its Millennium Development Goals for population health, such as reduction of under-five mortality and maternal mortality.

Rwanda also achieved a reduction in the incidence of HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis infections in the last decade. Starting in 2018, Rwanda launched a new journey of eliminating hepatitis C virus (HCV) as a public health threat by 2023, a target that is now more than 50% met.

Rwanda is one of the 194 countries committed to eliminating viral hepatitis B and C as a public health threat by 2030 by increasing testing coverage to 90% and treatment coverage to 80% globally, targets established by the World Health Organization (WHO). Many people think this ambitious plan is impossible with less than 10 years to go until the deadline, even in high-income countries like Canada. After all, there are numerous obstacles, like limited resources for purchasing tests and drugs, lack of support or leadership for HCV elimination in some countries, and now the COVID-19 pandemic.

Rwanda’s elimination efforts

Rwanda is among a small number of countries globally that have committed to eliminating hepatitis C earlier than 2030, despite their limited resources. Their elimination plan was launched at the end of December 2018, with goals to screen about seven million of its population aged 15 years and above and to treat more than 112,000 patients with chronic hepatitis C, with a budget of about 45 million US dollars. Funders of this plan include the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, domestic funds from the Government of Rwanda, the WHO, the private sector and other partners.

By November 2020, more than four million Rwandans had been screened for HCV, which is over 57% of the goal of screening seven million. Of those screened, 84,007 tested positive for HCV antibodies, 41,620 tested positive for HCV viral load, and 38,980 began treatment (1), while in May 2021, about 51,000 patients were already treated for HCV, which is about 50% of the 112,000 people targeted to be treated. It seems highly likely that the remaining people may be treated by the end of 2022 (2).

A cascading approach

The journey to arrive at this success was not without obstacles. From the establishment of Rwanda hepatitis program and its technical working group in 2012, followed by policy and guideline development (3), each step of the journey had to be carefully planned and performed. Training of healthcare providers was conducted in a cascading approach, beginning with specialists in internal medicine from the four largest referral hospitals in 2015, to more than 1,500 healthcare providers from all health facilities in Rwanda, including nurses, laboratory technicians, pharmacists, data managers, general practitioners and specialists by the end of 2020.

These trained healthcare providers screened about 4.3 million people in Rwanda (about 62% of the target) and treated 51,000 patients with chronic hepatitis C (about 50% of the target). HCV screening was provided strategically, starting with key populations like people living with HIV, incarcerated people and female sex workers. In 2017, they expanded testing to the general population aged 45 years and over, and then finally to all people over 15 years of age visiting any healthcare facilities.

Different strategies to achieve one goal

To achieve elimination, many different approaches were employed. From the start of the hepatitis program, the Rwandan community was engaged in prevention by participating in screening and by raising awareness among all populations about the burden of hepatitis C.

Hepatitis services were integrated into pre-existing HIV/AIDS care by using platforms for HIV testing, like ELISA and PCR machines, to support HCV testing as well. Moreover, funds allocated to HIV, as well as healthcare providers specialized in HIV services, were also engaged in HCV testing and treatment.

Decentralization was another key factor in the progress of the elimination plan. Traditionally, hepatitis C services, from testing to treatment, were provided only by certain specialists in referral hospitals. Today, testing is expedited using rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) at health centres and nurses are able to prescribe hepatitis C treatment and follow up with patients during and after treatment.

Leadership involvement was crucial in the implementation of the HCV elimination plan by facilitating the mobilization of funds and the coordination of country-wide activities.

Partnerships with different institutions, including non-governmental organizations and the private sector, helped in the negotiation of price reductions for tests and drugs. This allowed the Rwandan ministry of health to purchase RDTs at USD 0.65/test, PCR tests at USD 9/test and 28-day direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) at USD 60/dose.

A strong monitoring and evaluation infrastructure allows Rwanda to closely track the progress of the HCV elimination plan, with main indicators illustrating the efficacy and value of different interventions.

In the beginning of 2016, people who tested HCV-positive and people on DAA treatments were recorded in Excel sheets and registers, then sent to the Rwanda Biomedical Centre for analysis and decision-making. From 2019, with the support of Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI), HCV indicators were introduced into a health information system, recording data electronically at each HCV screening facility, PCR hub and treatment centre, and sending results to the centralized system. The hepatitis program is using this system to produce national dashboards to rapidly and consistently update on HCV elimination efforts.

What Canada can learn

As healthcare in Canada is not administered at the federal level, it is unlikely that Canada could have a national hepatitis C elimination program exactly like Rwanda’s. However, Canadian provinces have much to learn from the successes that Rwanda has achieved with limited resources and in a short amount of time. Rwanda has particularly excelled at integrating hepatitis services into existing infrastructure, which is something that could be very feasible at the provincial level across Canada. Evaluations of the Rwandan HCV elimination program are ongoing, which may provide further insights to be applied in Canada.

Currently, Rwanda is on track to achieve hepatitis C elimination before 2030, a feat that many high-income countries may not achieve. This African country has shown how involvement of all parts of the hepatitis response, starting with the community to the leaders, can help foster success. Rwanda has shown other countries that even with limited resources, viral hepatitis elimination is possible.

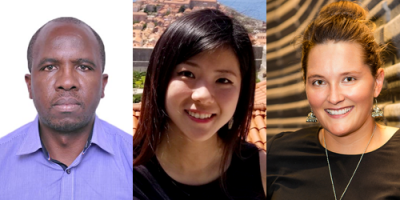

Dr. Jean Damascene Makuza is a medical doctor with a master’s degree in epidemiology and is currently a PhD student at the School of Population and Public Health at the University of British Columbia and trainee with Canadian Network on Hepatitis C (CanHepC). In his 12 years of experience, he has led programs in HIV, sexually transmitted infections, viral hepatitis and cervical cancer prevention and control in Rwanda. At the B.C. Centre for Disease Control (BCCDC), under the supervision of Dr. Naveed Janjua, his research looks at treatment uptake for patients screened for hepatitis B and C in Rwanda, as well as treatment outcomes for patients HBV mono-infected and HBV/HCV co-infected.

Dahn Jeong is a PhD candidate at the School of Population and Public Health at the University of British Columbia. Her doctoral research examines the benefits of direct-acting antiviral treatment for HCV infection, specifically in relation to extrahepatic manifestations. Dahn is a PhD trainee with the Canadian Network on Hepatitis C (CanHepC) and is also supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Sofia Bartlett, PhD, is a senior scientist for sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections (STBBI) at the BCCDC with the clinical prevention services program. She is an investigator with the B.C. Hepatitis Testers Cohort (BC-HTC) and the Canadian Network on Hepatitis C (CanHepC).

References

- Coalition for Global Hepatitis Elimination. “A global tour of options for scaling-up HCV testing to reach elimination goals.” Hep Test Webinar Series. 2020. p. 1–4.

- Medicines Patent Pool, Unitaid. “10 years left to eliminate viral hepatitis – what now, what next for uptake in hepatitis C treatment in low- and middle-income countries?” In: Webinar on HCV treatment access for low- and middle-income countries. 2021.

- Mbituyumuremyi A, Van Nuil JI, Umuhire J, Mugabo J, Mwumvaneza M, Makuza JD, et al. “Controlling hepatitis C in Rwanda: A framework for a national response.” Bull World Health Organ. 2018;96(1):51–8.