Ending the epidemic for whom?

Ending the HIV epidemic in Canada in five years seems like an ambitious goal, but it is now in fact a target being advocated by a group of public health and HIV advocates in a new document published by the Canadian Foundation for AIDS Research (CANFAR). I am one of the authors of that document, which acknowledges the necessity of addressing racism and structural violence. But, except for support from a couple co-authors, I am dispirited by the co-authors’ failure to be clear about the difference those systemic and structural issues make, to inspire determination in addressing them, and to illustrate what is at stake and what it means to address racism and structural disadvantage.

This optimistic projection – ending HIV in five years – is largely based on the knowledge that new prevention technologies such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and ‘treatment as prevention’ have demonstrated success at dramatically reducing new infections in countries such as the United Kingdom. The full effect of these technologies requires better access to HIV testing, care and treatment.

However, experiences from these countries deserve further reflection and action, particularly as they relate to African Canadians and other population groups affected by ongoing systemic racism. With antiretroviral treatment and PrEP, evidence from the United States and the United Kingdom show that Black populations in those countries experience lower initial rates of viral suppression or significantly higher rates of virologic failure and viral rebound.

There is also the issue that those therapies may be somewhat less accessible to Black communities than mainstream white populations. It is unlikely that new interventions to improve access to HIV testing and treatment will work for African Canadian communities that are effectively excluded from efforts to develop them.

These disparities in access to treatment and treatment outcomes, often driven by inequality and social determinants of health, reveal that HIV elimination cannot be achieved among marginalized populations with PrEP and ‘treatment as prevention’ alone.

Structural drivers of HIV can’t be resolved in five years

Ending the HIV Epidemic in Five Years acknowledges that an important (if not urgent) priority includes addressing racism and the structural forces that undermine well-being and increase vulnerability to HIV among some priority populations. Yet, five years is a short time to address these structural issues, meaning that the epidemic may persist among these groups even after victory would appear to have been achieved (or after victory has been declared).

Why are decision-makers generally reticent to address structural issues in any substantive way? Issues such as racism and poverty are perceived as too difficult or expensive to address in the short or medium term. Instead of attending to the systemic oppression and structural conditions that reproduce inequality, decision-makers promote “behaviour change” strategies based on discourses that pathologize disadvantaged communities. And of course, it is also politically and professionally expedient to ignore these communities and the issues that affect their well-being.

What the end of the epidemic will look like

So what does it mean to end HIV in five years (or even by 2030, as UNAIDS suggests), if structural and systemic issues remain as they are? We may anticipate that HIV may cease to be a major public health issue among population groups that are better served by the social determinants of health. But what about the rest?

Once victory is declared under those circumstances, resources may be withdrawn or diverted from the populations that are still struggling with HIV, that continue to be disadvantaged by social oppression and structural forces just as before.

These considerations all lead to the same place – the systemic and structural issues will cease to be urgent or important issues, and may simply disappear (or be made to disappear) from the list of priorities. Instead of engaging affected communities in good faith, decision-makers may devise interventions that merely preserve the status quo, which are bound to fail African Canadian communities.

Starting down a different path

This situation is not inevitable, but a more favourable outcome requires commitment to making a difference. As a start, I am proposing a companion document to Ending the HIV Epidemic in Five Years.

This project, implemented under the direction of stakeholders from Black and other racialized communities, would help ensure that decision-makers understand what’s at stake, and would provide a point of reference for the advocacy efforts of the affected communities – to hold stakeholders to account and facilitate transparency.

Ending the HIV epidemic in five years may be a laudable goal, but without an end to the epidemic for everyone, it’s not over.

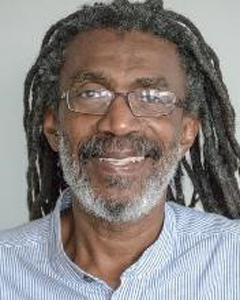

Winston Husbands, PhD, is senior scientist at the Ontario HIV Treatment Network, and adjunct professor at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, and at the Faculty of Health, York University. He works to mobilize research, community and other stakeholders to address and resolve crucial issues that affect the health and well-being of African, Caribbean and Black communities, especially in relation to supporting community responses to HIV.