Prison health is public health: The right to hepatitis C prevention, diagnosis and care in Canada’s correctional settings

As a follow-up to our progress report in 2021, we at Action Hepatitis Canada (AHC) decided to take a more in-depth look at the policy changes needed for priority populations for viral hepatitis elimination. Our goal is to release a progress report update every other year, and in alternate years to release a report on one of the priority populations. For our first of these priority population reports, we focused on people who are incarcerated. Prison Health is Public Health: The Right to Hepatitis C Prevention, Diagnosis, and Care in Canada’s Correctional Settings was released on March 31, 2022.

Why focus on people in federal and provincial correctional facilities?

People who are incarcerated (PWAI) are identified as a priority population for hepatitis C care, as they are 40 times more likely to be exposed to the virus than Canada’s general population.

In addition, people who are released from incarceration often face barriers to accessing health care in the community. While no one should ever have to be in the correctional system to receive healthcare, for many, their incarceration may present an opportunity to access health services including prevention, screening, early intervention and treatment programs. This kind of access will improve individual and public health outcomes.

The delivery of hepatitis C care to people in correctional settings in Canada is essential to hepatitis C elimination.

How was this report written?

A committee of AHC members who work with PWAI came together to create this report. In our first meeting, we set three priorities:

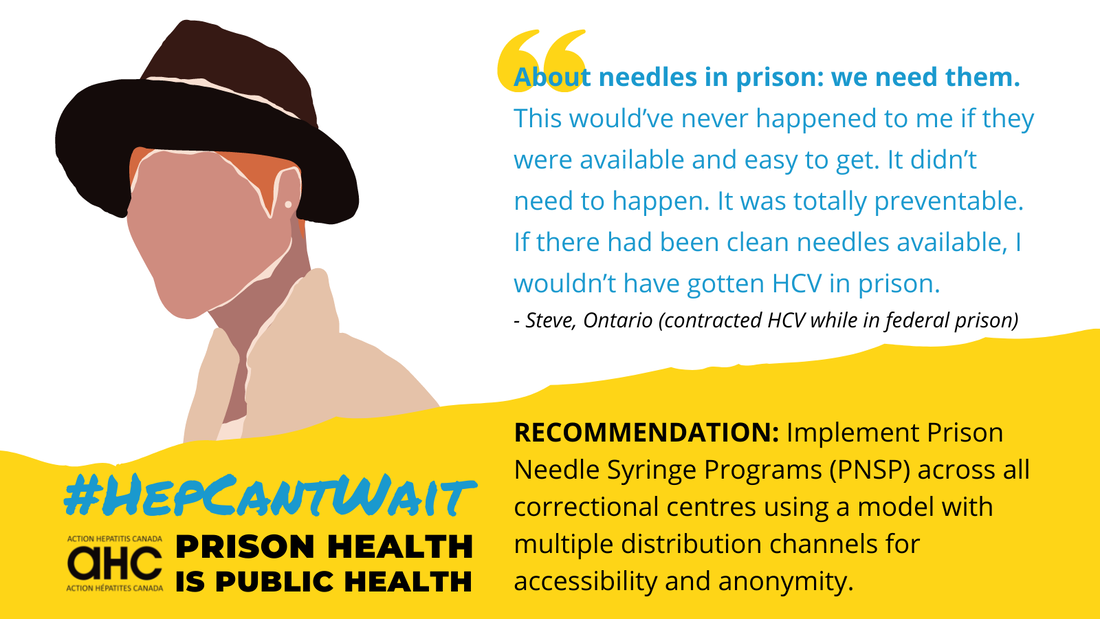

- centre the voices of lived experience

- come to the topic from a rights-based approach

- focus on hepatitis C, but in a realistic way that acknowledges the many shortcomings in the provincial and federal correctional systems and considers the whole person

With these guiding priorities, we set up interviews with seven individuals who have the experience of both living with hepatitis C and of being incarcerated. We also undertook a review of existing relevant research. We then pulled together the findings from both to create the report.

I want to acknowledge that as the author of the report, I do not have this lived experience, and I saw my role in this process as one of a convener and curator of the input from the topic experts, packaging these critical perspectives and findings into an advocacy tool that is accessible to allies and policy-makers alike.

What is in the report?

The report consists of several components, such as information on the right of PWAI to receive care and how the identities of PWAI might intersect with other priority populations like people who use drugs, Indigenous people, gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men, immigrants and newcomers to Canada and older adults. It also examines the current situation in different correctional systems and provides overarching guidelines and recommendations at the federal, provincial and territorial level. We have also shared excerpts from interviews conducted with PWAI: all these testimonials are highlighted in blue text throughout the report.

What is the current state?

At the federal level, the Correctional Service of Canada (CSC) could be well positioned to eliminate hepatitis C in people incarcerated within federal correctional institutions by 2030, with best practices such as:

- universal hepatitis C screening

- universal access to treatment

- harm reduction services

Significant scale-up of harm reduction services is still needed to maximize the benefits of treatment and avoid reinfection.

At the provincial and territorial level, the same standard of healthcare is not available to people in correctional centres as what people are getting in the local community settings of their provinces, and significant disparities in hepatitis C care exist across provincial correctional centres. Hepatitis C elimination is unlikely to occur in the Canadian provincial or territorial prison system by 2030 unless significant changes are made.

What are we recommending?

The report includes a set of overarching guidelines for healthcare in correctional settings, followed by six recommendations for the federal government and six for provincial/territorial governments.

Here are our overarching guidelines for healthcare in all correctional settings:

- an equivalent standard of care to what is available in the community, including harm reduction services

- person-centred

- trauma-informed

- culturally safe

- informed by people with lived experience

- run by peers (where available and applicable)

The following are recommendations we are making to the federal government:

- Implement prison needle syringe programs (PNSP) using a model with multiple distribution channels for accessibility and anonymity.

- Implement overdose prevention sites (OPS).

- Improve accessibility and acceptability of opioid agonist therapy.

- Review policies and implement training and education to promote health promotion and harm reduction, including hepatitis C and other sexually transmitted and bloodborne infections (STBBIs), for both PWAI and staff.

- Improve discharge planning to include linkage with community resources including healthcare.

- Develop national guidelines for STBBI testing that could be applied in correctional centres, both federal and provincial.

The following are recommendations we are making to the provincial and territorial governments:

- Transfer healthcare responsibility to the ministry of health (where not yet done).

- Improve accessibility and acceptability of opioid agonist therapy (OAT).

- Implement prison needle syringe programs (PNSP) across all prisons, using a model with multiple distribution channels for accessibility and anonymity. This could be complemented by a suite of harm reduction services that mirror what is available in the community, including OPS.

- Offer universal STBBI testing to everyone admitted in all correctional centres, with informed consent, within 72 hours of admission.

- Offer treatment to everyone diagnosed with chronic hepatitis C and a reflex referral to community-based supports, with consent, for continuity of care regardless of length of stay.

- Improve discharge planning to include linkage with community resources including healthcare.

Download the full report and find shareable images here.

Jennifer van Gennip is the executive director for Action Hepatitis Canada. She lives in Barrie, Ontario, and specializes in advocacy communications for non-profits.